Training Science Series #1 - Why We Focus on Capacity Training…to Eventually Go Really Fast

This is an article series designed to help further educate my Performance Coaching clients, but also anyone interested in learning how to train more successfully. If you are interested in getting fitter -- irrespective of whether you are a novice or regular athlete -- then please read through this series and learn more about the endurance training process. I also hope to welcome you onboard as your performance coach one day if you need mentoring to reach the summit of your athletic potential!

Understand the Process to Commit 100% to the Process

Part One - Introduction

Part Two - The Utilization Problem

Part Three - Overtraining Syndrome (OTS)

Part Four- Advice for Beginner Runners

Part Five - Aerobic vs Anaerobic Fitness

Part Six - The Aerobic Base - Capacity Training 101

Part Seven - The New Science of Fat Adaptation

Part Eight - Introduction to Threshold Training

Part Nine - A Brief Introduction to Heart-Rate Zone Training

Part Ten - How to Choose Which Zones to Train in Regularly

Part Eleven - Peaking: When to Enter a High Intensity Training Phase

Part Twelve - Keeping the Ego in Check and Sticking to a Long-Term Plan

For many decades, a battle has raged in endurance sports about how much Capacity versus Utilization training is optimal for endurance performance. The debate surrounds how much of each form of training is appropriate when considering the high-level performance – and longevity – of an athlete.

Capacity Training (also known as Aerobic Base Training) is training aimed at improving the long-term performance of an athlete through a high volume of low-intensity training that develops a long list of metabolic adaptations tailored for endurance performance. An endurance athlete can never have too much aerobic capacity.

Utilization Training (also known as High Intensity Training: HIT or HIIT) is needed if an athlete wants to peak and achieve their best results. It typically mimics the specific demands of races and includes faster pace tempo and interval workouts that rapidly improve the short-term performance of an athlete. Utilization training seductively results in rapid fitness gains, but also reduces the athlete’s capacity unless it is offset with capacity training.

Countless variations of the two training methods have been tested by countless athletes and coaches across multiple endurance sports for almost a hundred years. New stuff is tried all the time, bad ideas are reworked, and the good ideas rise to the top through results where it matters: in world-class competitions. There was no shortage of motivation either as the importance of the Olympic games brought with it high stakes financial and political outcomes, especially between rival superpower states such as Germany, United States and Russia etc…. Huge amounts of money flowed into sports science to test an array of specific training approaches as countries tried to outmatch their rivals. An article on Training Peaks explains:

Running in the US dealt with this debate at the turn of the century after the United States’ success of the 1970s and 1980s gave way to an era of disappointing results in the 1990s and early 2000s. The later era coincided with a shift by many coaches and athletes away from a capacity oriented training system to one relying heavily on a utilization approach. Rowing had this debate back in the 1980s after a dramatic change in the coaching philosophy in Germany which abandoned the utilization approach in favor of one based on building capacity. This switch soon led to German domination of the sport. Cross country skiing had a similar internal debate when, in 2004, Norwegian exercise physiologist Dr. Jan Helgarud caused a sensation with his outright denunciation of capacity training as useless.

These two training model have been well-tested by millions of athletes and thousands of coaches in the ultimate laboratory: the competitive arena. While some noteworthy holdouts exist, the approach of relying primarily upon building Capacity before applying limited amounts of Utilization training has largely won out in this contest of ideas.1

The outcome was pretty clear: athletes who train with a large volume of low-intensity capacity training – with smaller doses of event-specific high-intensity utilization training performed close to races – have superior race and performance outcomes than athletes who don’t train with this approach. The best results tended to come with a balance of 80-90% capacity training, sprinkled with 10-20% of utilization training across the overall yearly volume.2 It doesn’t matter if the endurance sport is rowing, cross-country skiing, cycling, track, or trail-running etc… the same training balance invariably wins out when it comes to optimally maximising human endurance performance.

If an athlete’s goal is only very short-term performance for a few years before fading away, then a higher volume of utilization training can be successful, albeit temporarily. However, this is often only successful at the highest level if the athlete has a previous foundation of capacity training to work from and is not a complete fitness novice. High utilization focused athletes frequently suffer from Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and drop away from the top pretty quickly, rarely making it back, such is the debilitating effect it has on one’s physiology.

Many people wonder why certain elite athletes can keep producing at the highest level without burning out despite heavy race schedules and massive levels of weekly training loads. Kilian Jornet will be mentioned often throughout this document, and he is probably the finest example of a high capacity training athlete, renowned for his longevity and his astoundingly high volume of daily training. His single-minded dedication to the pursuit of mountain focused capacity training, along with his early introduction to endurance activities in his upbringing, is the fundamental reason why he is arguably the world’s greatest endurance trail runner.

Jornet typically trains for long hours in the morning at very low intensity (for him), and again in the afternoon for around an hour (on some days). On other days, he only trains once, but these days he is typically out training all day long. Then he has a heavy racing calendar where he dominates the sport and typically only takes two weeks off a year for recovery. Why doesn’t he burn out? People often put this down to a freak combination of genetics, however, Jornet was fortunate that he started capacity training at a very young age (around 3-years-old) and then progressed a little more every year of his life since then. He also closely listens to his body and tests it all the time for what works and what doesn’t.

Jornet’s parents were mountain guides and took him hiking regularly at high altitudes from a very young age. He was said to have boundless energy. Starting his aerobic base training at such a young age no doubt had a profound affect on his developmental physiology. Once into his teenage years, his strongly developed fitness base saw him identified as a strong endurance prospect, and was given further coaching by experts in Catalonian academies designed to develop ski-mountaineering and trail running athletes (these schools are unique to certain countries in Europe and they are fantastic nurseries for trail running and skimo talent).

From those coaches, Jornet learnt the right way to train. He also had an obsessive infatuation with training science from a young-age which meant he understood proper training principles long before most people do or ever will. While other kids at 13-14 years old were only sometimes listening to their coach’s advice and pushing their body hard because it was “more fun” that way, Kilian understood the big picture and was already looking a decade ahead. At that young age, he was listing out all the races he wanted to win (posting it as a vision board in his room) and was listening intently to what the coaches were teaching him. By 17 he enrolled in university at Font-Romeu in France, taking sports science, along with studying anatomy and physiology. He learned the theory behind what the coaches were telling him, and then he carried on coaching himself to this day using what he learnt, motivated by a dogged single-mindedness and ravenous appetite for success.

Kilian’s training is often unstructured in appearance because he doesn’t do a lot of conventionally structured workouts due to his love of adventure, but what he does overall in a weekly, monthly and yearly load is very structured in application and methodology. He also knows when to push and when not to in his daily training outings, and what impact this has on his performance in races.

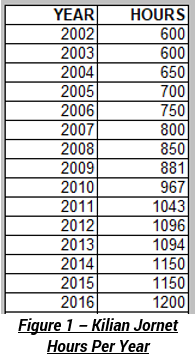

Jornet was meticulous in creating training logs and logging all his training and carefully reviewing the metrics and stats each year. In his training log, he was able to sum up the number of hours per year he spends training, which he then consistently incremented (see Figure-1). Knowing this data, he could ensure the next year was always doing a little more than the last. Now 32, Jornet essentially progressed through a consistently incrementing 29-year capacity base-building progression that makes my brain hurt just reviewing it.

Even back in 2002, 600 hours equates to an average of almost 2 hours training every day of the year, which by 2016, increased to an average of 3.5 hours per day. In this process, there are several years where he effectively plateaued his training time volume, but there are no years where he went backwards (until a recent high-profile skimo crash where he broke his leg).

Jornet deserves more credit than he gets due to his exceptional understanding of sports science and his strong discipline toward not overusing utilization training. While he does have a physiology that is potentially genetically geared toward success, its hard to say how much of these genetics are epigenetic changes, simply as a product of his upbringing and consistency in athletic progression. Jornet is not unbeatable as other athlete’s have shown, so undoubtedly someone else put through the same process – with the same mentality and dedication to the pursuit over 30 years as Jornet did – may yield similar outcomes in physiological adaptation and performance.

Many people wrongly assume Jornet is doing a lot utilization training given his high training volume and his incredible mountain running speed. However, due to his massive aerobic base, those training demands are still in the realm of capacity training stress levels to his physiology. He would not be able to sustain 3.5 hours of training per day for very long if he was doing high-intensity training each day, because his high intensity is extremely fast. Proponents of utilization training might argue Jornet might even be a more superior athlete if he lowered his training time per day and increased his intensity. However, Jornet has no doubt tried this approach given his frequent experimentation testing out different training metholodigies and approaches. The proof is in the pudding. It is the long days on his feet that condition his body for success.

In previous years, Jornet rarely needed to push to the level of utilization training intensity other than for a few short weeks at the start of the trail running season after coming off skis (which he uses throughout winter for his training). His heavy race calendar meant he could simply use races (almost each weekend) as his only form of utilization training. Jornet says about 80% of his yearly volume is capacity training, which is the recommended amount and a number utilized by most world class athletes.3,4

Jornet’s hours per year are not dissimilar from other elite athletes. Elite professional cyclists train upwards of 25+ hours a week, with a steady diet of long 3-6-hour bikes ride as a daily basis as part of their training.5 They actually have to do a little more hourly volume than Jornet, because sitting on a bicycle is so efficient physiologically compared with the impact loads of running. Elite cross-country skiers require 1000 hours a year or more as minimum to hit the world class level as well.6 What Jornet does is not common in professionals who have the time available to train.

Novice athletes often try to replicate the volume of elite athletes and burn out, failing to realise it took a long time for professional athletes to gradually rise to the level of 1000 hours a year or more. Scott Johnston, along with colleague Steve House, partnered with Jornet to advise on the best training methodology for mountains endurance sports in the book, Training for the Uphill Athlete. In it they write:

Kilian’s legendary ability to handle a huge volume of work (and much of it very hard) is a result of his decades of capacity-building training. It can be very tempting to try to simulate the training of elite athletes. Doing so without their years of capacity-building work will mean that you are actually doing Utilization Training.7

The final sentence is a crucial point to understand. What is capacity training for one athlete, will be utilization training for another – and there is no shortcut around it. The more elite an athlete becomes, the wider this cavern appears to the ordinary fitness mortal. For example, the utilization training of a novice athlete wouldn’t even come close to the maintenance load capacity training of a world-class athlete.

World class athletes can handle a lot more utilization training than novice athletes, but the demands of utilization training on the body grow significantly. Therefore, the fitter you become, the more polarized your training should become. The hard days will be really hard, but the easy days have to be really easy speeds (to the athlete – but maybe not to most observers) to ensure the athlete can sustain the high weekly training volume.

Another good example is Eluid Kipchoge, currently the world’s most impressive marathon runner. In preparation for this sub-2-hour marathon event, he logged an incredible training volume. His “easy” recovery runs of 10km in the afternoon, following more intense morning training, were performed in 40 minutes at 4:00min/km pace.8 For many people, that pace is fast enough to be utilization training, or at least a daily diet of it would be. To Kipchoge’s aerobic physiology, this pace is a recovery speed that barely makes him break a sweat, allowing him to recover from his more intense training sessions without adding an additional fatigue.

Remember that intensity doesn’t just equate to speed and heart-rate but also volume. A novice athlete cannot just expect to step in and do 1000 hours of training from a foundation of nothing and expect to get through it without fatigue or injury. They must start where everyone else has to start, which is said to be around the 300 hours a year mark for novice athletes.9

Therefore, we cannot use other people to model our training workouts on specifically, but we can certainly follow the same training principles they used to get there. Everyone should be training like Jornet, just through methodology, structure, and progression, not the specific workouts, volume, and speed he does. If you can actively work to apply those exact same principles and mentality he used, and match the appropriate level of capacity training to the fitness level of where your body presently sits, then this is historically shown to be the most optimal pathway to developing your full athletic potential. It requires patience, a long-term outlook toward training and to be constantly working off a training plan that measures progress. The problem is most people are short-term focused in their training goals and plan their training to maximise their short-term fitness.

The stark observation from all this is, you might not actually be 5-7 years away from your athletic potential, but more like 15 years, which is why many endurance athletes peak around 30 if they started at school, or in their 40’s if they started in their 20’s. Anything beyond a 10% increment on training time volume per year is not recommended. So, assuming 300 hours a year is the starting volume, a 10% increase per year would take approximately 7 years for a novice to build up to 600 hours of volume, and a staggering 15 years to get to Jornet’s present 1200 hours a year, assuming no injuries or other setbacks halt the yearly progress (this timing is probably the best case scenario!).

Ultimately, the best outcome is always starting young, but you can still achieve great things if you start at any age in life by getting started. No matter what age you start, each year should build upon the last and it doesn’t take long to start getting really fit if you can maintain good consistency. Training more often doesn’t mean you will become more tired, if its done properly you should build up fatigue resistance and actually gain some energy as you get fitter.

After many years in my 20’s suffering chronic back pain, knee cartilage damage, and chronic fatigue syndrome, I started running at 28. Seven years later, at age 35, I was only 5 minutes slower than Jornet in a 40-minute Vertical KM race in Chamonix France at a reasonably high altitude I was unaccustomed to (I am from Australia land of no high-altitude mountains). Furthermore, I was about 40-minutes behind him in one of the toughest marathons in the world, the Mont Blanc Marathon, which I was quite happy about given it was the furthest I had ever run (even including training). My progression from novice – to the bottom end of the “elite” category – matches the 7-year theory pretty soundly. However, my gap to Jornet consistently widened the longer the race duration, due to my far inferior aerobic base and musculoskeletal conditioning compared to his. I was able to close the margin to within 10-15% in shorter races with a heavy utilization focus for maximising performance in Vertical KM races, but I did pay a price from that suffering Overtraining Syndrome (to be discussed shortly) in the years that followed before I truly understood how to train properly.

Next Article -> Part Two - The Utilization Problem

2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4621419/

3 https://www.kilianjornet.cat/en/media/train

4 https://www.sweatelite.co/kilian-jornet-ultramarathon-training-insights/

5 https://cyclingmagazine.ca/sections/feature/family-full-time-job-and-racing-like-a-pro/

6 http://ccsam.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/LTAD-guide-CCC.pdf

7 https://www.trainingpeaks.com/coach-blog/training-for-the-uphill-athlete-capacity-vs-utilization-training/

8 https://www.sweatelite.co/eliud-kipchoge-full-training-log-leading-marathon-world-record-attempt/

9 Training for the Uphill Athlete. 2019. Scott Johnston, Steve House, Kilian Jornet.